The latest story from Michèle Laframboise is a novella set among the clouds, where humans have settled in large, floating cities after devastating climate conflicts. In this enlightening Q&A, learn more about Michèle’s interest in flying, as well as the risks of living at high altitudes. Check out “Maragi’s Secret” in our [May/June issue, on sale now!]

Asimov’s Editor: How did this story germinate? Was there a spark of inspiration, or did it come to you slowly?

Michèle Laframboise: I battled against pollution and the senseless destruction of nature well before pollution’s impact on the Earth’s climates was widely known. My formative years as a geographer, then engineering student, inspired me some disturbing futuristic scenarios.

“Maragi’s Secret” is set in one such future where most of humanity is living on floating cities in the upper troposphere layer. After the climate wars, the Earth’s surface has become unlivable, forcing humanity to migrate up in large, well-equipped vessels. Several wild bird species have followed the humans and their animals raised for food and dairy.

AE: Is this story part of a larger universe, or is it stand-alone?

ML: Maragi’s Egg is stand-alone for now, but this post-apocalyptic world is also the setting of a larger work-in-progress. My formation brings a more scientific perspective to the sometimes magical steampunk vessels (how can such massive steel mastodons fly?) set in an alternative 19th-century era.

In the first novel, currently done, the main protagonist meets an adult Maragi in an clandestine hospital. Immediately, I knew she had a heart of gold. The first thing I wrote about her was an odd streak of sunspots coursing across her face, like a flight of birds. I became instantly curious as to what this person went through as a youngster.

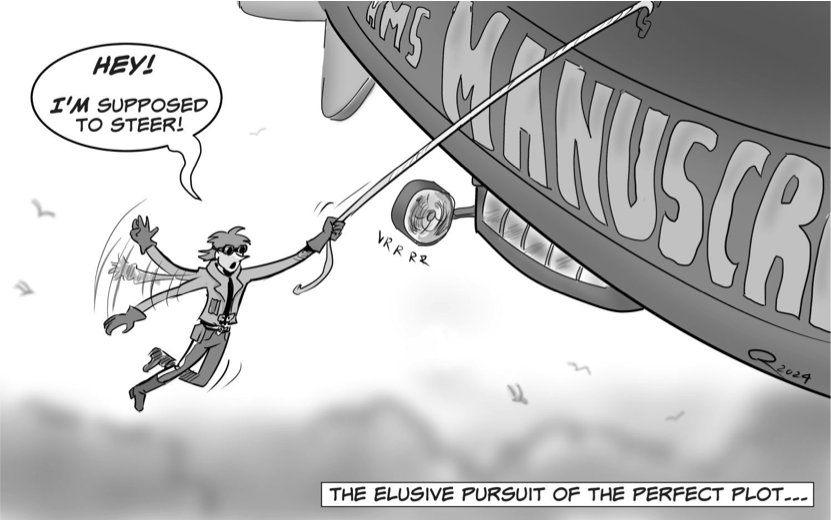

AE: Did you encounter plotting turbulence?

ML: Yup! Such a world represents a fantastic challenge for a science-fiction writer.

On the technical side, my dear father helped me devise some buoyancy characteristics, and the volume of the lifting gas. He was very ill at the time, but intellectually alert, so I kept his advices and my sketches in my writing carnet.

Since I started pondering this future, I read a lot about our history of dirigibles. The huge scale of the cigar-shaped balloons was an eye-catching wonder at the time. I read about the crash of the R-101 dirigible in 1930, brought by a collusion of engineering mistakes, socially acceptable drinking and political ambitions. Disregarding risk was seen as a daring quality, not at all like today’s caution. And drinking and flying!

When the main lifting gas was flammable hydrogen (more easy to produce than helium), the risk of explosion was considerable. The spectacular explosion of the Hinderburg on its landing in 1937 is graved on the memories. (Note that today’s Zeppelins are held aloft by hot air or helium.) Non-flammable helium is an inert gas that modern tools allows us to pump, but it is a non-renewable resource, a gas so light it escapes the Earth’s atmosphere. Hot air is another alternative.

AE: Can humanity survive in high altitude?

ML: There are tons of obstacles to living in altitude.

First, there is the problem of the dwindling oxygen partial pressure. If some of you have seen pictures of the Everest with a long line of people waiting for their turn at the summit, you’ll notice how all of them wear oxygen masks. (You’ll also notice corpses here and there, frozen to death.)

Second, the cold! The minus-twenty degrees C is a normal temperature for the altitude. In the day, the sun heat up the cities’s streets and houses to a balmy five to ten degrees.

Third, the low air pressure brings a host of health concerns documented by medical teams working with mountain-dwelling people. Our migrated humans living in high altitude will be subjected to not one, but a host of health concerns.

At 60 % of the sea level oxygen concentration, hypoxia manifests itself with exhaustion, dizziness, shortness of breath, headaches and, as the heavier symptoms walk in, nausea, vomiting, insomnia . . . On the long term, fluid accumulation in the lungs pulmonary and cerebral oedema (swelling of brain) are expected, what probably affected Maragi’s mother.

The more deleterious effects of hypoxia impacts the decision-making ability of the brain. A depletion of oxygen as low as a 30% from the sea level affects your judgement. Even before the R-101 accident, the effects of flying in high altitude were already known by the WWI pilots. Meaning, your judgement is warped, and obsessive ideas takes root. Memory is impacted, too.

So a dirigible crew would breath faster to replenish their lungs’ oxygen, and adult citizens usually avoid running on the streets of cities. Only the youngsters would be able to exert themselves going up and down the riggings.

Humans have been able to live in altitude: the sherpas and the Andean people have gradually adapted to the low-oxygen environment. The Andeans, adapted since 10,000 years, carry more dissolved oxygen in their blood.

AE: What about the social aspect?

ML: In the upper troposphere, you can’t have defined borders. So you’d have groups of cities drifting along the latitudes, clusters that replace countries.

Every floating city needs a huge lifting volume, repatriated between several balloons. It is a very difficult equation and the administrators have to balance the weight . . . especially when the unshakable rats and birds multiply! Add daring scavengers to the mix, bringing up surface fuel and antiques market, and you have a challenging world-building.

AE: Michèle with that imagination, did you get the opportunity of flying yourself?

ML: Yes. Once in a small Cessna 53, with my father at the commands. Often with the airlines; as a former geographer, I love gazing at the landscape under me, its endless wonders at the dendritic shapes of rivers and rumpled mountains.

And, by myself, I will never forget jumping from a hill, soaring suspended under a hang glider wing. Even for a short distance, I felt connected to the valiant pioneer of the start of the XXe century, whose heavy biplanes barely lifted off the field of daisies . . .

Now, I fly on the wings of my imagination, sustained by the wonders of science.

AE: Where can we find you?

ML: I’m not flying that high, my office is in a basement, but you might find me in conventions near Toronto, or online:

Author website: Michele-laframboise.com

Indie House: Echofictions.com

Twitter: Savantefolle

Facebook: LaframboiseSF

Instagram: michelesff

One comment