by Hûw Steer

Hûw Steer returns to the pages of Analog with the story “Great Martian Railways” in our [July/August issue, on sale now!]. In this blog post, follow along as Steer discusses the scientific possibility of operating a railway system on Mars.

Let’s establish something straight away: I am not a scientist. I haven’t studied science in well over a decade. I am a historian by training and trade; I could name several laws of the Roman Republic but struggle with the laws of physics.

This is not to say that I’m completely scientifically illiterate. It certainly does, however, explain “Great Martian Railways,” my story in this edition of Analog, in which I place nuclear-powered steam trains on the surface of Mars.

In this case being a historian works in my favour, as I combine steam trains (invented in the 1800s), nuclear reactors (invented in the 1940s) and Mars (invented in the 4,500,000,000s). But I am no man of science, and thus it is entirely possible that all of the following explanation will be completely and laughably wrong. I therefore point at the part of the sign that says Science Fiction and Fact and beg forgiveness from anyone reading this who actually knows what they’re talking about.

I did, however, do a fair bit of research to get this story done. So let’s dig into how this very silly idea might actually work, shall we?

I Like Trains

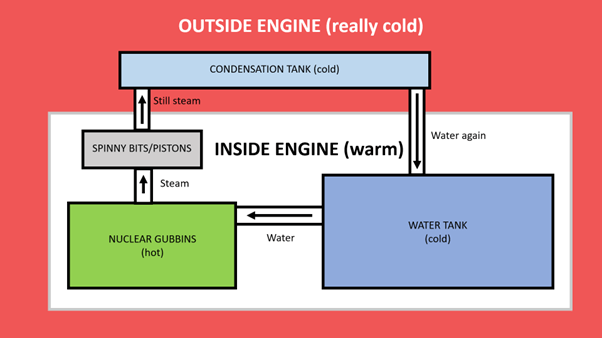

The ultimate genesis of this story comes from when I first learned what nuclear power was, probably when I was about 10 years old. We were given a very brief outline of Glowy Metal Gets Hot, Boils Water, Spins Thing, which was filed away with lots of other random facts in the overflowing cabinets of my child’s brain, not to be consulted again for some time. But at some point in the years between primary school and adulthood, the neurons holding this fact brushed up against the neurons that hold my lifelong love of steam railways. (I grew up near Wales; between endless heritage railways and more castles than anywhere else in the world it’s a wonder I had time to eat and sleep.)

The neurons touched, a spark flared. I put the two together, and realised that if a nuclear reactor is, in essence, a very big and very complicated steam engine, then modern science should be morally obligated to stick one on wheels and turn it into a locomotive. Steam trains are, after all, objectively superior to any other form of railed transport, though maglevs are allowed to come in close second. There is a wonderful analogue (heh), clunky beauty to them, the physical heft of pistons and the clatter of iron infinitely more satisfying than any modern sleek, smooth machine. Steam engines are to modern trains as vinyl is to an mp3: technically inferior, but so much more. [1]

But just because something’s old-fashioned doesn’t mean it can’t be brought kicking and screaming into the future.

Under Pressure

The moment of specific inspiration for Great Martian Railways was actually a brief moment of bad science. The Martian atmosphere is a bit rubbish, with about 1% of Earth’s pressure. Aha! This means that water would boil almost instantly in a Martian atmosphere! You wouldn’t even need a nuclear reactor to get steam!

What’s that? The complete lack of pressure means that the steam wouldn’t even have the force to flap a bit of paper, let alone push a piston? …fine, that might be a minor inconvenience.

It was at this point that my locomotive’s design began to properly take shape. Any steam engine on Mars would have to be a fully sealed unit to maintain the high pressure needed for said steam to drive a turbine or piston. That’s fine, this is Mars: everything humans build needs to be sealed. But the steam does need to go somewhere or the engine will explode. Again, no problem—in fact a solution to another problem at the same time. There’s not an awful lot of water on Mars,[2] as far as we know, so you wouldn’t want to be blasting plumes of steam into the air. But that rubbish Martian atmosphere is nice and cold. Have your reactor steam flow out into a tank on top of the locomotive, where the freezing conditions will make it condense back into liquid water, ready to be boiled again. A closed system, minimising water loss and maintaining pressure at the same time.

(Obviously there would be water loss, and probably a lot of issues with pressure, but I will again point at the Science Fiction sign and apologise.)

For a nuclear reactor, the only fuel you’re really burning in the short-term is water, after all. The actual Glowy Metal Bits will last lifetimes—the scarce resource for the Great Martian Railway is the steam itself. Inside the engine it must stay, then, causing the biggest loss of all, which is the inability to use the steam to whistle like a proper train. It wouldn’t work in the rubbish Martian atmosphere anyway, of course, but it’s still a shame. Add another reason to the list in favour of terraforming the Red Planet…

It’s The Future, Just Go With It

The nature of nuclear reactors as we currently understand them does bring me to some of the more handwaved elements of the story, though.

- How’d you get a nuclear reactor that powerful to Mars?

- How’d you make that nuclear reactor small enough to put on wheels?

Small nuclear batteries—RTGs—are sent into space all the time, but they are small, and on a locomotive like the one I had in mind they weren’t going to do much more than power the bells, let alone the whistles. It needed to be a properly powerful beast, which meant hauling an awful lot of radioactive material all the way from Earth to Mars, which would take an awful lot of rocketry.

Unless Martian colonists conveniently happened to find uranium deposits under Mars’ red soil, which they could then mine and refine on Mars itself. That would be much easier to do, and to fit into a rapidly expanding word count, and it is thus what has happened on the near-ish future Mars of Great Martian Railways.

Being in the near-ish future, and given that nuclear reactors are currently getting smaller all the time, it also seemed plausible enough that one could be made small enough to roll. It’s still big, don’t get me wrong—hundreds of tonnes of metal and graphite and all that jazz. But it needs to be, to some degree, to keep everything firmly pressed down onto the rails in the reduced gravity and maintain traction. Even with reduced weight there’s still an awful lot to push—but being big and beefy means that the reactor is powerful enough to push itself and more besides. And it’s got to push itself a long way.

Why Do Any Of This?

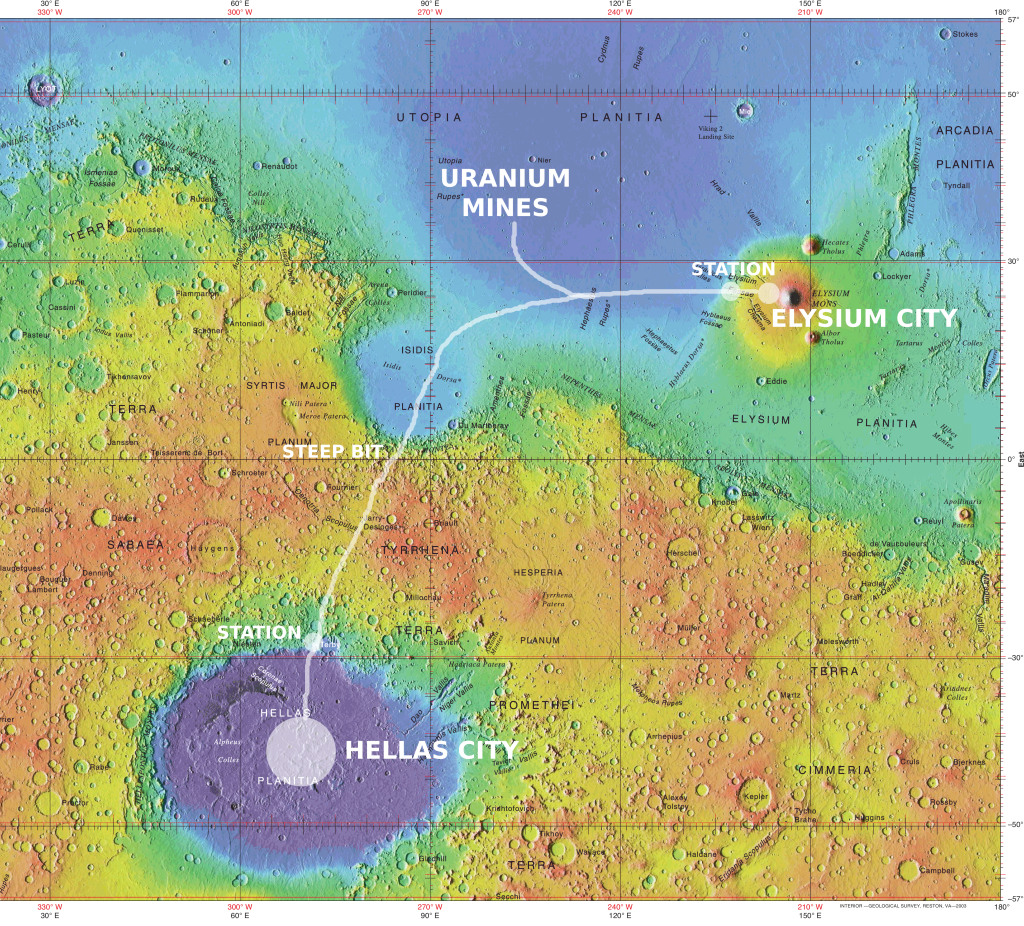

As much as I was immediately satisfied with bringing the central concept of ‘steam trains in space’ to life, to make this story a story I needed something else. I needed an actual reason for these trains to exist. That meant breaking out the Ordnance Survey map of Mars and doing some navigating.

This Mars had to be a settled one—not terraformed, still a Red Planet, but a Mars where humanity had very much made its home. Dome cities litter the vast red desert, each a colossal undertaking, each built in very different environments. A surface dome-city nestled against a big mountain just seemed cool, and no self-respecting SF author can pass up the opportunity to name a city Elysium. (Alas, much of the description of Elysium was a victim of the cutting-room floor.) So that was one there. But just as on Earth, resources are scattered—uranium mines, say, aren’t going to necessarily always be next door. And with sandstorms and radiation and the rather large volcanoes, not every Martian settlement would want to be on the surface. Sitting at the bottom of a crater, say, would provide a bit of protection from the Martian elements—so the next city along, sprawled out across the bottom of the biggest crater on the planet, was Hellas. Sketching a journey from one to the other, avoiding the steepest terrain, gave a journey of over 3000km.

Too far to drive in rovers, too little atmosphere to easily fly, no water for boats… well, would you look at that? It seems Mars needs a robust, reliable transport system to carry people and heavy loads from one major settlement to the other. If only humanity already had a heavy-duty transport solution ideally suited to crossing vast expanses of largely flat terrain…

And this story is of course presenting only the first stretch of rails. There are other cities on this Mars, other resources to reach and transport—and little in the way except for sand and hills. The more I wrote of this story, the more I realised that this idea might actually work.

One-Track Minds

“Science isn’t about why – it’s about why not.” – Cave Johnson (2011)

There is a human element in this story, of course, and there would have to be a particular kind of human element to get an idea like this even slightly off the ground. There is a certain bloody-minded stubbornness necessary to truly commit to anything as vastly difficult as colonising Mars… or, a couple of centuries ago, building railways. This isn’t just pushing the boundaries because you must—it’s doing so because you can. There are other solutions to Martian transport beyond a largely analogue machine that was superseded decades ago even in our modern era. Even with a nuclear reactor strapped to the rails, there are still so many other options that would, with our current standards of space travel and colony concepts, be more obvious and probably more feasible.

But when has humanity ever done the easy thing? When have we ever picked the simple option? If we had, we wouldn’t be in space in the first place. If we had, then the Mars of Great Martian Railways would still be empty. The fact that I was presenting a colonised Mars meant that these pioneering people had to be there—and that meant they’d be bringing their ideas with them.

And with a whole new world at their fingertips, with so much space—figurative and literal—to explore new ideas… why not railways? Why not nuclear steam trains? Why not try ideas like these? What seems mad and impractical on Earth need not be so on a new world with a new start.

*

I hope, dear reader, that at least some of this makes actual sense. I hope that the actual nuts and bolts of this story do what I think they do. But while I may not know that much about science, I do know about ideas. I know how they spread, how they persist, even centuries later. I know how the best ideas never truly die. And given the right environment, the right time, the right space… who knows what ideas might come around again? I might not be the person to implement them—but someone will be. Sometimes, the old ways might actually be the best.

[1] If you are unfortunate enough not to have experienced this feeling, either seek out your nearest heritage railway or read Terry Pratchett’s Raising Steam. He captured it perfectly. GNU.

[2] Except in Doctor Who.

Lighted most of the story (a page turner) but the that steam-turbine driving generator would have been a better bet. Back in the early 50s the US A.E.C. had all types of atomic usages proposed including a nuclear powered train with reactor/turbine replacing the diesel.

LikeLike

OOPS did not proof should read – Liked vice lighted.

LikeLike