by Alec Nevala-Lee

In this exclusive feature for The Astounding Analog Companion, Alec Nevala-Lee draws parallels between the “DOGE Kids” of 2025 and the scientists who worked closely with government during the Cold War. Nevala-Lee pays special attention to physicist Luis W. Alvarez, who, contrary to a number of his contemporaries, questioned the role of “hard” sciences in government without the influence of “soft” sciences that actually studied the “‘infinitely more complicated system’ of human society.” For more on Alvarez, check out Nevala-Lee’s latest book, Collisions: A Physicist’s Journey from Hiroshima to the Death of the Dinosaurs

The destructive campaign by the Department of Government Efficiency to hack the federal bureaucracy—unofficially overseen, until recently, by Elon Musk—has been unprecedented in its scope and cruelty. It also looks strangely familiar. In February, Charlie Warzel and Ian Bogost wrote an article for The Atlantic that described it as “the logical end point of a strain of thought,” born in Silicon Valley, that sees coding skills as “proof of competence in any realm.” As one anonymous official put it, “There’s this bizarre belief that being able to do things with computers means you have to be super smart about everything else.”

While this might feel like a recent development, it’s actually a degenerate version of a mindset that dates back to the Cold War. During World War II, scientists played an indispensable role in programs like the Manhattan Project and the deployment of airborne radar. After the war, the desire to preserve this pool of brainpower led to the creation of advisory groups like the RAND Corporation, along with countless panels and committees where scientists could offer policy advice. Physics, in particular, had been so crucial to the Allied victory that physicists were treated as authorities far outside their original areas of expertise.

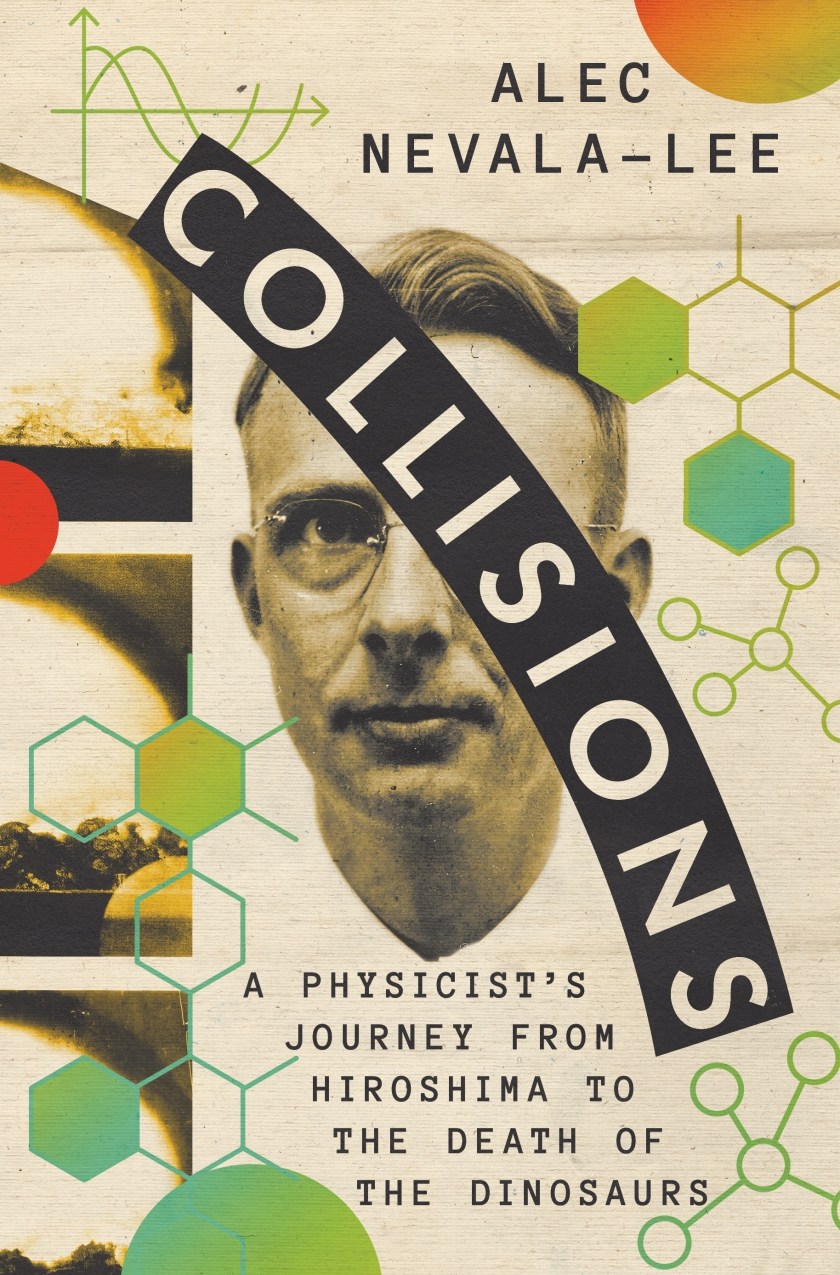

I became interested in this story while writing Collisions, my biography of the physicist Luis W. Alvarez, who thrived in this world. Unlike the mostly young and inexperienced “DOGE Kids,” he was the kind of man who would be a valuable asset on any team. After working on wartime radar and the atomic bomb, he spearheaded the engineering of the liquid hydrogen bubble chamber, a groundbreaking tool for experimental physics that won him the Nobel Prize. Toward the end of his life, he partnered with his son Walter to argue that the extinction of the dinosaurs was caused by an asteroid strike, igniting a debate that was resolved in his favor only after his death in 1988.

Alvarez, in short, had good reason to have a high opinion of his abilities, and the government felt the same way. Along with consulting for RAND, he served on committees that looked into everything from submarines to spy satellites. In 1961, he collaborated with Daniel Ellsberg—the analyst who later leaked the Pentagon Papers—to write a report on Vietnam. When President Kennedy asked for his thoughts, however, Alvarez hedged his response: “Most people feel compelled to tell the president what they think he’d like to hear. I was no exception; I’d have had difficulty saying that our policies were disastrous.”

Throughout it all, Alvarez was aware that if he ever gave an inconvenient answer, he probably wouldn’t be invited back. He came to specialize in finding apparently objective facts to support the official narrative on controversial issues like the Kennedy assassination. Alvarez was never less than honest, but he avoided conclusions that might threaten his privileged status. As one of his colleagues noted of such scientific consultants, “They like to be called in and asked for their counsel. Everybody likes to be treated as though he knew something.”

The man who said this was J. Robert Oppenheimer, a longtime friend whose downfall gave Alvarez an unforgettable lesson in the price of dissent. In 1949, after the Soviet Union detonated an atomic weapon, Alvarez joined other scientists in calling for the development of a thermonuclear bomb, which Oppenheimer feared would lead to a devastating arms race. To cut off his influence, Alvarez testified as one of the government’s witnesses—along with Edward Teller—at the notorious security hearing that destroyed Oppenheimer’s public career.

While Oppenheimer openly expressed misgivings about the role of scientists in public policy, Alvarez only hinted at his own concerns. After receiving the Nobel Prize in 1968, he told a delegation of students in Stockholm, “People often say to me, ‘I don’t see how you can work in physics; it’s so complicated and difficult.’ But actually, physics is the simplest of all the sciences; it only seems difficult because physicists talk to each other in a language that most people don’t understand—the language of mathematics.” Outside the lab, he said, it was harder to predict outcomes in the “infinitely more complicated system” of human society.

Alvarez was implying that the traditional scientific hierarchy, which viewed “hard” sciences like physics as more difficult than “soft” ones like sociology, actually had it the wrong way around. As it happened, a pair of Berkeley professors arrived at a similar conclusion at almost exactly the same time, just a short walk away from the physics department where Alvarez spent much of his career. At the College of Environmental Design, Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber drew a distinction between the “tame” problems of the hard sciences, with their clear rules and objectives, and “wicked” social problems that lacked any obvious stopping point.

Alvarez was implying that the traditional scientific hierarchy, which viewed “hard” sciences like physics as more difficult than “soft” ones like sociology, actually had it the wrong way around.

As Rittel and Webber warned, “The social professions were misled somewhere along the line into assuming they could be applied scientists—that they could solve problems in the ways scientists can solve their sorts of problems. The error has been a serious one.” Much the same mistake can occur when these social questions are posed to experts in the physical sciences—to say nothing of software developers. To their credit, Alvarez’s generation of physicists rose to the challenge of tackling the seemingly insurmountable technical problems presented by the war. In Silicon Valley, companies have the luxury of focusing on attractive ideas while ignoring others. Social media, for instance, was less a response to a real need than a product of the tools and revenue models that coders understood.

Even under such favorable conditions, new technologies—as we all know by now—can have unintended consequences. This is doubly true of reckless responses to the unavoidable problems that government policies are meant to address. Alvarez, at least, was a deeply serious, genuinely brilliant man. DOGE, by contrast, simply applies a technological veneer to the sidelining of experienced officials in favor of a pipeline of “super high-IQ” opportunists who can advance the goals of the Trump administration. Simultaneously, the disciplines that might provide actual insights into these issues—the humanities and social sciences—are pressured to purge themselves of alternative perspectives. And without a diverse range of voices, these fields can become equally complicit in the process of democratic backsliding.

During the Cold War, advice from scientific experts was used, among other things, to justify a massive nuclear buildup. (Alvarez claimed to “enthusiastically support” the doctrine of mutual assured destruction.) There’s little reason to expect that the outcome today will be any better, unless we manage to learn from the mistakes of the past. Addressing the students in Stockholm in 1968, Alvarez spoke candidly about “the difficulties that will confront you when you have the responsibility to make decisions that will affect the future of mankind.” He concluded, “I wish you the best of luck and good judgment when that time comes. The world would be a much better place in which to live if my generation and those that preceded it had had more of those two essential attributes—good luck and good judgment.”