by Alec Nevala-Lee

In 1963, Isaac Asimov published The Human Brain, his fifty-fifth book, which he later remembered as one of the most challenging projects that he had ever undertaken. Shortly afterward, he received a call from an interviewer asking him to appear on the radio as an authority on the brain. He quickly declined, explaining that he wasn’t a brain expert, and when the interviewer pointed out that he had just written an entire book on the subject, Asimov replied: “Yes, but I studied up for the book and put in everything I could learn. I don’t know anything but the exact words in the book, and I don’t think I can remember all those in a pinch.”

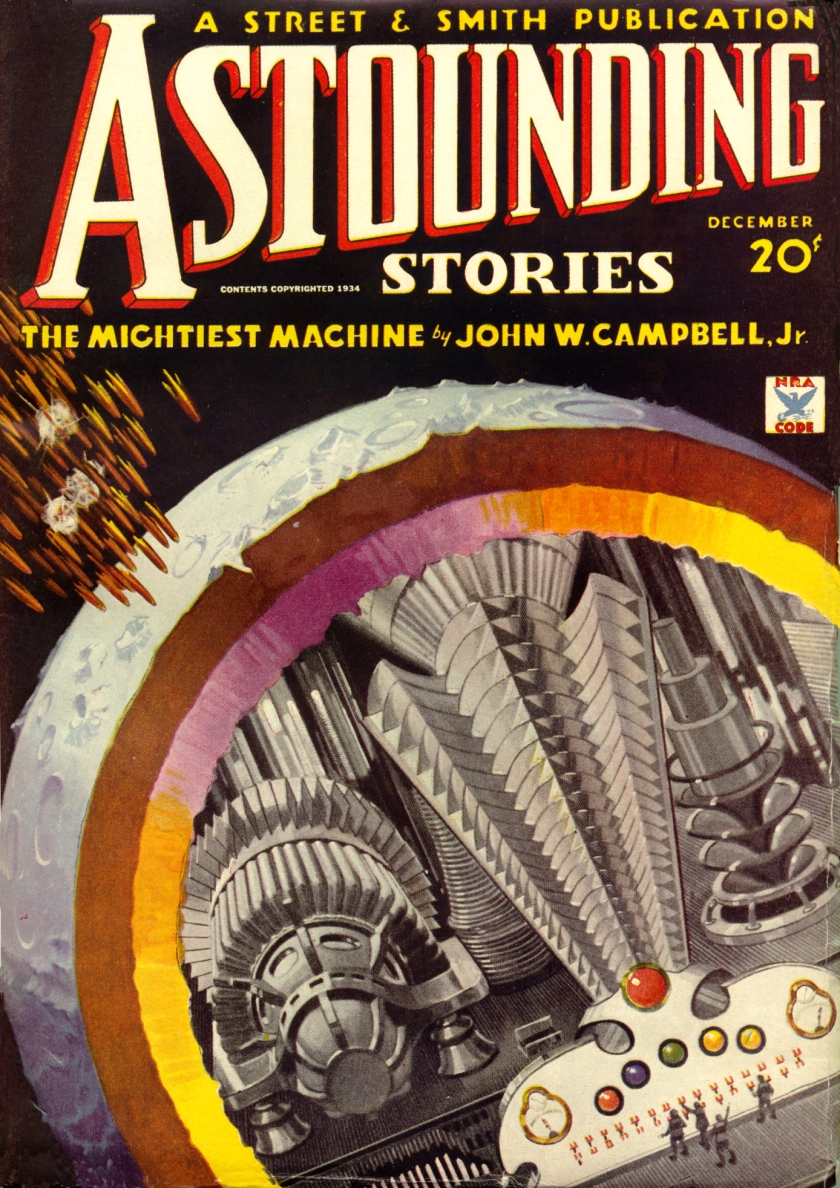

There are times when I’ve felt the same way. My book Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction is scheduled to come out in October, and writing it only confirmed how little I really know. About three years ago, I realized that there had never been a full biography of Campbell, the legendary editor of Astounding and Analog, and since this was clearly a book that had to exist—and I happened to be available—I decided to give it a shot. I’m very happy with how it turned out. But there were also moments when I wasn’t sure if I would be able to pull it off.

Writing about Campbell—a fascinating but deeply problematic figure—would have been hard enough in itself, but the project soon became even more complicated.

And I had good reason to be concerned. Writing about Campbell—a fascinating but deeply problematic figure—would have been hard enough in itself, but the project soon became even more complicated. It expanded to encompass the careers of the editor’s three closest collaborators, including Hubbard, whose importance to the genre came less through his fiction, which was mostly mediocre, than through his impact on the lives of others. It was also the story of Astounding, which meant that I had to be familiar with both the magazine and its competitors, since I couldn’t write about it without taking into account everything else that was going on in the field at the same time.

I had been reading and writing science fiction for most of my life, but there were huge gaps in my knowledge, and it was obvious that I couldn’t cover everything. As a result, I had to lay down a few ground rules. I would read all of Campbell’s fiction, including the unpublished stories in his papers at Houghton Library at Harvard. (This included an early draft of his novella “Who Goes There?”—later filmed as The Thing—with more than thirty pages of previously unseen material, which I hope will eventually see the light of day.) It also seemed best to work through most of Hubbard’s science fiction and fantasy, of which I’ve probably read more by now than anyone who isn’t actually a Scientologist. I did much the same, with far greater pleasure, with Asimov and Heinlein.

When it came to placing their works in context, I had to be more selective. I began by compiling a list of stories from several classic collections, including The Astounding Science Fiction Anthology, The Astounding/Analog Reader, Analog’s Golden Anniversary Anthology, Adventures in Time and Space, and the three volumes of The Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Gradually, I also acquired copies—in digital form or in print—of every single one of the hundreds of issues of Astounding, Unknown, and Analog published in Campbell’s lifetime. I couldn’t read them all, but I tried to live up to the advice that the biographer Robert A. Caro attributes to his mentor Alan Hathway: “Turn every goddamn page.” And I did.

In the end, along with thousands of letters and other primary sources, I wound up reading about six hundred works of fiction, ranging in length from just a few pages to the gargantuan Battlefield Earth. Sometimes this meant revisiting stories that I had read long ago, but many were new to me, and I devoted three months to consuming as much as I could in chronological order. In practice, I had to skip around a lot, and I didn’t get through all of it. There are still big missing pieces in my acquaintance with the works of the golden age—particularly outside Astounding—and my grasp of the field all but ends with Campbell’s death in 1971.

But it isn’t an exaggeration to say that it changed my life. Before I started, I had never read such authors as E.E. Smith, A.E. van Vogt, or Eric Frank Russell, whose Sinister Barrier is now my favorite science fiction novel of all time. (“The Spires,” my story in the current issue of Analog, March/April 2018, features a character named after Russell, and the plot is openly inspired by his fascination with the paranormal researcher Charles Fort.) I discovered such stories as “E for Effort” by T.L. Sherred, “Izzard and the Membrane” by Walter M. Miller, and “Noise Level” by Raymond F. Jones; I was awed by the partnership of Henry Kuttner and Catherine Moore; and even Hubbard had a few—a very few—stories that I came to admire.

There were times when it felt as if I were mainlining the whole history of science fiction, or at least a significant chunk of it, and I’ve already seen the effects on my own work. (The story that I’m writing now is an homage to James Blish’s “Surface Tension,” which I read for the first time through this list.) Working through so many stories over a short period of time only makes me more aware of how much I have yet to read, and the fact that it had to be centered on Campbell means that it left out many important voices. Filling in the blanks will take the rest of my life, and I’m not even close to done. But I’ll give myself an E for effort.

Alec Nevala-Lee’s book Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction will be released by Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins, on October 23, 2018. His novella “The Proving Ground,” which originally ran in Analog, will appear in the upcoming edition of The Year’s Best Science Fiction, edited by Gardner Dozois. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oak Park, Illinois, and he blogs daily at www.nevalalee.com.

As far as I am concerned, Alec’s work in ANALOG ranks high among the magazine’s best of the last ten years. Looking forward to this new “Astounding bio” later this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Ken! That means a lot to me.

LikeLike

Science Of Sciences

I am a big science fiction fan. Was really influenced by some great authors in my younger day. It satisfied my need to know what was and what could be. That included knowing what sciences were currently observed, tested and reported to better understand directions of what may become. My opinion is Science Fiction is first and foremost…science told within a story. Not of the various attached genres of horror, comic book heroes or magic. For me it was always about the science. When an artist or scientist peaked my curiosity upon a subject that was predominate to the storyline…that was when I went looking for the current documented findings. How did that come to be and why…where does the science originate to motivate a storyline? Some ideas are grand in scale both in character and scope. Others are small products and abilities just taken for granted. Some make it to the future years later…others become conspiracy theories. So when I go to the science fiction section…please do not categorize 1000 ways to die terribly in space, mutated super professors becoming aliens or parlor tricks on broom sticks as the hard-core sale. I want to observe todays possibilities and the possible observations of tomorrow. Give me the science of the scientific futures.

https://aeon.co/essays/how-science-fiction-feeds-the-fuel-solutions-of-the-future

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alec, you give yourself an E, but I’m going to go ahead and give you an A+. An incredible effort yields incredible results. Brace yourself: The SF field will not stop thanking you for years to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I grew up on the stories and authors you mention here, though many of them were first published a generation before I read them. I rather envy you the experience of freshly discovering some of these. Of course even when I first encountered them it was often like finding fossils preserved in amber, though there was a lot of continuity between the WW2 period and the fifties/sixties of my childhood. As it happens, the time of Campbell’s death in 1971 is roughly where I place the dividing line between what I think of as the Digital Age and the Analogue Age that I grew up in – not just a shift of technology and material artifacts, but also of social trends and of the way people behave, interact, and imagine themselves in day to day life.

It pains me to think of all the lovely stories and authors that are now fading into oblivion, so thanks for your contribution to SF histories. I look forward to reading it. If you ever feel the urge to continue the endeavor, I suppose the logical next step would be to explore the H. L. Gold / Fred Pohl Galaxy mag, with its shift toward social and psychological themes and The Magazine of Science Fiction and Fantasy with its more literary bent.

And then there’s the closely connected but parallel history of early SF fandom. Ever read The Immortal Storm by Sam Moskowitz? (I love the grandiose title.) Fortunately for those who are interested, several well known authors such as Pohl, Asimov, and DeCamp published autobiographies that touch on this subject and era.

LikeLike